Fueling Your Flow: A Comprehensive Guide to Nutrition and Menstrual Health

Women’s Health – You Asked, We Answered!

Fueling Your Flow:

A Comprehensive Guide to Nutrition and Menstrual Health

Summary:

During the follicular phase, estrogen levels increase, resulting in greater insulin sensitivity and glucose utilization (use of sugar and carbs as fuel). Therefore, it is recommended to choose foods rich in carbohydrates, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes. Furthermore, the body requires more protein in this phase to support the growth of new follicles (in the ovaries). Vitamin C intake is important to assist in the absorption of iron, which is crucial during menstruation because of loss of blood – excessive amounts of which can lead to anemia. (9, 10).

The ovulatory phase is marked by a surge in luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone. During this time, it is beneficial to increase intake of vitamin D, calcium, and magnesium to support bone health. Moreover, it may be helpful to increase your intake of essential fatty acids such as omega-3, which may help alleviate menstrual pain and cramps (10, 11).

During the luteal phase, the body requires more energy, and it is recommended to consume more complex carbohydrates, such as whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. Additionally, it is vital to increase your intake of vitamin B6 (bananas, pistachios, potatoes, turkey, chickpeas, fortified cereals) (5), which may help alleviate premenstrual syndrome symptoms. Moreover, increasing your intake of zinc and magnesium may also help reduce menstrual pain and cramps (12, 13).

Full Article:

Historically, females have been underrepresented in research studies related to the menstrual cycle. In fact, of over 5200 papers published in six prominent exercise science journals from 2014-2020, only one third of research subjects were female, and only 6% focused specifically on the impact of the menstrual cycle on exercise performance. While there is not much published research yet on nutrition throughout the monthly hormonal fluctuations, we know that these variations in endogenous sex hormones can affect dietary status. The dynamic shifts in sex hormone levels throughout the menstrual cycle differ dramatically from that of males, and thus warrant further exploration of nutrition tailored specifically to the menstrual cycle. (1)

The menstrual cycle can be thought of as two phases (Figure 1). The follicular phase is characterized as day 1 of menstrual bleeding until ovulation, while the luteal phase takes place following ovulation. Within one cycle, there are 4 different hormonal combinations. The early-follicular phase (menses, the 1st 5 days) is defined by low estrogen and low progesterone, while the late-follicular phase (the 14-26 hours prior to ovulation) is characterized by high estrogen and low progesterone. In the ovulatory phase, there is medium estrogen and low progesterone. The mid-luteal phase (7 days following ovulation) is marked by medium estrogen and high progesterone. (1)

Figure 1. Phases of the menstrual cycle shown with body temperature, endometrial, and hormonal status (13).

These sex hormones have a role beyond solely reproductive status – they also regulate an array of physiologic processes, including dietary and energy needs. For example, higher levels of estrogen in the late-follicular phase may increase insulin sensitivity and promote carbohydrate metabolism, while higher levels of progesterone in the mid-luteal phase may increase appetite and promote fat storage. As a result, paying attention to nutrition throughout the menstrual cycle can help support overall health and wellbeing. (1)

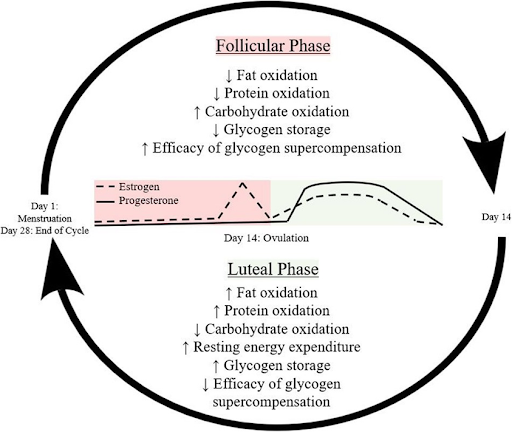

The sex hormones affect dietary preferences and nutrient utilization in different ways (Figure 2). Estrogen is presumed to suppress appetite. In the presence of estrogen, progesterone tends to have an appetite-stimulating effect. Metabolism of the carbohydrates and fat vary throughout the menstrual cycle. In the luteal phase, compared to the follicular phase, the body has a stronger tendency to use fat to fuel exercise and has increased storage of glycogen (the body’s storage form of carbohydrates) at rest. Utilization of proteins for fuel also increases in the luteal phase, and is thus surmised to contribute to the increased resting metabolic rate during this part of the cycle. Evidence suggests that daily calorie intake is greater in the luteal phase than the follicular phase (anywhere from around 90-530 calories/day on average in studies), though dietary studies can be challenging to interpret, due to potential inaccuracy of self-reported nutrition data. (1)

Figure 2. (For the science nerds!) Metabolic processes throughout the menstrual cycle. (8)

Inadequate intake of calories can result in detrimental health outcomes, such as menstrual irregularities (including absence of a period, known as amenorrhea), endocrinologic (hormonal – sex and other) disturbances, compromised bone health, poor athletic ability, and greater risk of injury and illness. (1)

The research space is also lacking data on the influence of diet on premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms, a condition that affects ~90% of women and affects mood, as well as causes physical symptoms (bloating, cramps, etc.) (5). Studies have demonstrated that consistent consumption of 1-3 grams of omega-3 fatty acids per day may reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression (8). A topic worth exploring is the effect of diet on dysmenorrhea – the painful lower abdominal cramping associated with a menstrual period experienced by 60-70% of young women. The pain is caused by the release of prostaglandins into the uterus at the commencement of menstruation, which stimulate uterine contraction. General recommendations for treatment and prevention of pain are oral contraceptive pills (aka birth control) and NSAIDs (such as Advil or Aleve). Because every form of medication is associated with side effects, and not everyone is a candidate for this type of therapy, it is important to explore the relationship between diet and menstrual pain, to determine if foods/nutrients exacerbate or relieve symptoms. (2)

Overall, a diet abundant in whole unprocessed foods is ideal for health in general, including menstrual symptoms. It has been found that eating meat and drinking cola are risk factors for dysmenorrhea, while vegetarian diets and/or fruit/vegetable consumption was linked to a decrease in estrogen activity and hence a reduction in the frequency of pain symptoms. (2) Additional studies have shown that consumption of fish oil (omega 3 fatty acids) are effective at relieving menstrual pain (4), and even more effective than ibuprofen at reducing severe pain in dysmenorrhea (3). However, the benefit of ibuprofen over consumption of fish oil (via diet or supplementation) is that ibuprofen can be taken at the start of symptoms for relief, whereas the fish oil requires consumption on a consistent basis for the benefits. In one study, women were treated with 1000 mg/day of fish oil during all days of the cycle for 60 days. The omega 3 fatty acids suppress the production of the prostaglandins that cause the uterine pain (3). Another study demonstrated that high consumption of sugars, desserts, salty snacks, caffeine, fruit juices, and added fat were linked with increased risk of dysmenorrhea (6). Another study focused on the effects of the Mediterranean Diet (MD) on symptoms found that women who ate less than two pieces of fruit per day were almost 3 times more likely to suffer menstrual pain (7). Consumption of olive oil was associated with decreased length of menstrual flow, which may benefit those who are anemic secondary to excessive blood loss (7). Additional nutrients recommended for menstrual-related pain and PMS symptoms are calcium (yogurt, almonds, kale, beans) (5), magnesium, vitamin E, vitamin B1 (thiamine), vitamin C (3), and vitamin B6 (bananas, pistachios, potatoes, turkey, chickpeas, fortified cereals) (5). The avoidance of salt, tobacco (3), caffeine, and alcohol (5) is recommended. Engaging in physical activity most days of the week may help regulate fluid status and improve mood (5). Therefore, lifestyle changes including exercise and a focus on fish oils, while limiting heavily processed foods are advised for reduction of (pre)menstrual symptoms.

In conclusion, being mindful of nutrition throughout the menstrual cycle can help support overall health and wellbeing. Although there is still much to learn about the specific nutritional needs during different phases of the cycle, these general guidelines can be helpful in ensuring that your body is receiving the nutrients it needs to function optimally.

Notes:

-

In this article, for brevity, female and male refer to those assigned female or male at birth (AFAB or AMAB), respectively, though we recognize and respect that female or male may in other contexts represent a range of individuals, and that not every AFAB or AMAB identifies as their respective assigned gender. It is our hope that our message is inclusive, and we welcome feedback on how to respectfully communicate with our audience.

-

For accessibility, in this article, “calories” refers to “kcal”, as most non expert readers are more familiar with the former terminology.

-

1 gram = 1000mg.

-

It is important to note that nutrition research is often conflicting, contradictory, and evolves as more data is available. To further complicate things, each person has an individual set of genetics, hormonal profile, environmental influence, etc. that affects nutrition status. Thus, it is difficult to give exact recommendations, or give promises that if you follow a certain eating pattern, you will find relief of symptoms. Always consult your OB/GYN or a dietitian if you have menstrual or dietary concerns, or before changing diet drastically, or adding supplements. Certain supplements can interfere with medications or health conditions.

References:

-

Michaela M Rogan, Katherine E Black, Dietary energy intake across the menstrual cycle: a narrative review, Nutrition Reviews, 2022;, nuac094, https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuac094

-

Ferna´ndez-Martı´nez E, Onieva-Zafra MD, Parra-Ferna´ndez ML (2018) Lifestyle and prevalence of dysmenorrhea among Spanish female university students. PLoS ONE 13(8): e0201894. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0201894

-

Rahbar, N., Asgharzadeh, N., & Ghorbani, R. (2011). Comparison of the effect of fish oil and ibuprofen on treatment of severe pain in primary dysmenorrhea. Caspian journal of internal medicine, 2(3), 279-282.

-

Harel Z, Biro FM, Kottenhahn RK, Rosenthal SL. Supplementation with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the management of dysmenorrhea in adolescents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996 Apr;174(4):1335-8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70681-6. PMID: 8623866.

-

Klemm, RDN, CD, LDN, S. K. (2021, April 5). Premenstrual syndrome. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Retrieved March 14, 2023, from https://www.eatright.org/health/pregnancy/fertility-and-reproduction/premenstrual-syndrome

-

Najafi et al. BMC Women's Health (2018) 18:69 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0558-4

-

Onieva-Zafra MD, Fernández-Martínez E, Abreu-Sánchez A, Iglesias-López MT, García-Padilla FM, Pedregal-González M, Parra-Fernández ML. Relationship between Diet, Menstrual Pain and other Menstrual Characteristics among Spanish Students. Nutrients. 2020 Jun 12;12(6):1759. doi: 10.3390/nu12061759. PMID: 32545490; PMCID: PMC7353339.

-

Wohlgemuth, K.J., Arieta, L.R., Brewer, G.J. et al. Sex differences and considerations for female specific nutritional strategies: a narrative review. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 18, 27 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-021-00422-8

-

"Dietary and lifestyle recommendations for the prevention of menstrual-related symptoms in adolescent girls." Nutr Res Pract. 2014 Oct;8(5):529-36. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2014.8.5.529.

-

"Nutrition and the menstrual cycle." Journal of Adolescent Health Care. Vol. 10, No. 5, September 1989.

-

"Dietary supplementation with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids reduces menstrual pain in adolescent girls - a randomized controlled trial." Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013 May;92(5):585-90. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12016.

-

"Premenstrual syndrome: nutritional and hormonal aspects." Annu Rev Nutr. 1990;10:233-57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.10.070190.001313.

-

Brown University. (n.d.). The Menstrual Cycle. Brown Medicine Pediatrics Residency. Retrieved from https://brownmedpedsresidency.org/the-menstrual-cycle/